By ASHEQUN NABI CHOWDHURY, journalist and former diplomat.

26/01/26

In the thirty‑five years I spent in the trenches of Bangladeshi journalism – 1983 to 2018 – I believed I had witnessed every possible face of repression. I endured the refined but unmistakable intimidations of the Ershad military regime, survived the partisan purges that swept through newsrooms during the Bangladesh Nationalist Patry (BNP)’s years, and watched the Awami League slowly tighten the noose through laws crafted to look democratic while functioning as instruments of fear. I thought I knew the full vocabulary of suppression.

But as I confront Bangladesh’s media landscape in the aftermath of the so‑called July Revolution of 2024, I am forced to confront a far more unsettling truth: nothing in our past prepared us for this. This “transitional era” is not a return to freedom, nor a continuation of authoritarianism – it is a volatile, shape‑shifting terrain where the old rules have collapsed and the new ones are being written by mobs, factions, and power brokers who answer to no one. For the first time in my professional life, the threat to journalism feels both everywhere and nowhere at once.

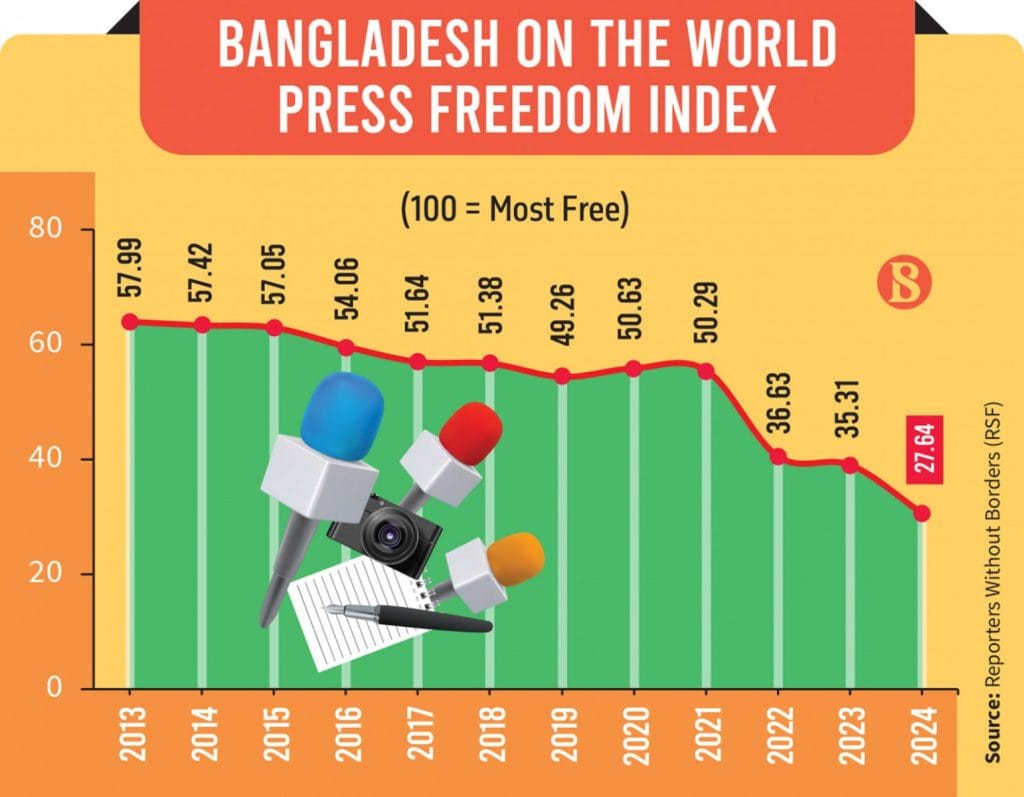

What we are witnessing today is no longer the familiar choreography of state‑managed censorship. It is something far more chaotic and infinitely more dangerous: a media ecosystem where threats no longer flow from a single centre of power but erupt from every direction at once. Angry crowds, politicised youth factions, vigilante groups, and opportunistic actors now wield intimidation with impunity, exploiting the collapse of centralised authority as their licence to terrorise the press. The latest assessments from global media watchdogs only affirm what many of us have sensed in our bones: this is the most perilous moment for Bangladeshi journalism in living memory.

.

” … how fragile freedom becomes when politics infiltrates the newsroom.”

When Hussain Muhammad Ershad’s quasi‑military government (March 1982-December 1990) seized power, the media operated under suffocating restrictions. I still remember being summoned to Gonabhaban, where his Private Secretary, a high-ranking army personnel, questioned me about my writings and my criticism of the regime. The atmosphere was tense, yet the meeting ended with a polite warning not to be “too harsh.” Over time, the environment shifted. Toward the end, the Ershad government grew noticeably more tolerant of the press. Even when newspapers across the country, including his own, went on strike against him, the response was relatively restrained, though sporadic targeting of journalists never fully disappeared.

After Ershad fell in the historic 1990 uprising, I hoped Bangladesh was finally turning a page, that freedom of expression would expand, not contract. But during the BNP government, led by Khaleda Zia, (February 1991–March 1995) many journalists perceived as supportive to the Awami League suddenly found themselves insecure. My wife and I were among them. The unlawful dismissals from our respective media houses had nothing to do with our work but everything to do with our beliefs. Losing jobs in that way was not just a personal and professional blow; it was a stark reminder of how fragile freedom becomes when politics infiltrates the newsroom.

During the BNP’s 2001–2006 tenure, the pattern sharpened, and journalists with opposing views, me among them, were systematically punished. By then, the cycle had become painfully familiar. Each dismissal felt personal, yet each one chipped away at the collective hope that journalism could rise above partisan battles. Those years taught me how profoundly political tides can shape the lives of people simply trying to speak their truth.

The Awami League’s periods in power, led by Sheikh Hasina (June 1996–July 2001 and December 2008–August 2024) carried their own contradictions. Many believed that a party so central to the nation’s independence would also champion a freer and safer environment for journalists. To its credit, the media landscape did expand dramatically: private newspapers, television channels, radio stations, and online platforms multiplied, and journalists’ wages improved through government-backed wage boards.

Yet beneath this outward growth, longstanding vulnerabilities endured. Laws such as the Digital Security Act, originally framed as a tool for ensuring cybersecurity, were frequently applied in sweeping and arbitrary ways. State actors, including police and administrators, as well as non‑state actors such as national and local political figures, used these provisions to harass media outlets and journalists. Political considerations continued to shape who enjoyed protection and who remained exposed, and journalists were still targeted for their views.

In contrast, two of the three caretaker governments, the first from December 1990 to March 1991 and the second from March 1996 to June 1996, offered rare periods of relative calm. Those brief intervals felt noticeably freer, with no significant instances of journalists being targeted or punished. They served as reminders of how different the media landscape can be when political interests loosen their grip, even temporarily.

The third interim government (January 2007 to January 2009) was a stark departure. It foreshadowed the dynamics of the current administration. Bangladesh’s press operated under emergency law, censorship, and military‑backed pressure, producing one of the most restrictive environments for journalists in the country’s recent history. Conditions eased somewhat ahead of the December 2008 election, but the two‑year period remains widely remembered as a major setback for media freedom. (Attacks on the Press in 2007 – Bangladesh: UNHCR, February 2008)

“The democratisation of intimidation, mob violence and rise of extremism … “

When Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus assumed leadership of the current interim administration in August 2024, the air was thick with the promise of a “discrimination-free” nation. It was hailed as a “new dawn.” But for the media and journalists, it has become a fragmented nightmare where centralized state repression has been replaced by something far more volatile: the democratization of intimidation, the mob violence and rise of extremism.

Under this interim government, the situation has deteriorated beyond anything seen under previous caretaker administrations, and even many elected governments. Before long, assessments from international watchdogs and domestic observers shifted sharply, exposing a far more alarming reality

Instead of delivering the meaningful reforms promised at its inception, the Yunus administration presided over a transition from centralised state repression to a fragmented landscape defined by mob intimidation, retaliatory litigation, and politically motivated administrative purges. What emerged was not the dismantling of coercive structures but a widening vacuum of authority, one in which mob violence, legal harassment, and institutional pressure became frighteningly routine.

The hostility toward the media, journalists, and free thinkers that has unfolded since this interim government assumed power extends far beyond individual suffering. It marks a profound deterioration in Bangladesh’s already fragile commitment to freedom of expression. And once again, I found myself targeted, this time not by an elected government, but by an interim administration that had pledged to build a “discrimination‑free” nation and uphold neutrality. The irony is impossible to ignore.

In many respects, this period has felt more reactive and at times more hypersensitive to media scrutiny than any other moment in Bangladesh’s recent history. The shift has been deeply unsettling, not only for journalists but for anyone who values open discourse.

From dictatorship to mob rule

As political polarisation intensified and extremist groups gained visibility, a new and chilling reality emerged: the mob began acting as a de facto regulator of the media industry. On 18 December 2025, Bangladesh witnessed the deadliest assault on its media since independence. Protesters, emboldened by a vacuum of state authority, stormed and set fire to the Dhaka offices of the country’s two leading dailies, The Daily Star and Prothom Alo. The attackers accused the papers of having links to a foreign country and branded them “enemies of the revolution.” They weren’t just burning paper, they were burning the very idea of independent inquiry, accusing the outlets of being “enemies of the revolution.” Despite repeated pleas for protection, newspaper authorities reported that security forces under the interim government failed to intervene or disperse the crowds.

UN Special Rapporteur Irene Khan described the events as the “weaponisation of public anger” and warned of a chilling effect on democratic life. The absence of accountability, combined with rhetoric from certain government advisers suggesting that journalists who had “legitimised fascism” would face consequences, has created an environment in which non‑state actors feel emboldened to target media institutions with impunity.

The physical risks to journalists escalated sharply after the fall of the Awami League. Data from the Rights and Risks Analysis Group shows that attacks on journalists surged by 230% during the first year of the Yunus administration compared to the final year of Sheikh Hasina’s government. Between August 2024 and July 2025, 878 journalists were targeted through physical assaults, criminal charges, and administrative restrictions.

The lack of thorough investigations into these killings and into the mob violence against media houses have reinforced the perception of a state either unable or unwilling to protect the press. Organisations such as the Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch, Fortify Rights, Tech Global Institute, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, CIVICUS and the International Federation of Journalists have repeatedly called for swift, independent, and transparent inquiries, but the interim government’s preoccupation with “revolutionary justice” and the approaching elections has left these appeals largely unanswered.

Financial and administrative control

Beyond physical threats, the interim administration deployed administrative tools to silence and marginalise media professionals. The Press Information Department of Bangladesh has cancelled accreditation of at least 200 journalists perceived as sympathetic to the ousted government, the legal system is being weaponised to conduct a sweeping purge.

Where earlier crackdowns relied on targeted arrests, typically dressed up as defamation, sedition, or anti‑state offences, the new pattern is far more expansive. Mass, catch‑all litigation now names dozens of journalists alongside political figures as supposed “abettors” of the July assaults, collapsing the distinction between reporting and wrongdoing.

This is censorship by other means. When a government cannot silence the pen through law, it seeks to cripple the writer through litigation, turning the courts into instruments of intimidation, financial ruin, and enforced silence.

The international community has grown increasingly alarmed by what many now describe as a systematic purge of journalists perceived as sympathetic to the former Awami League government, coupled with the interim administration’s failure to curb mob violence. Human rights organisations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have criticised many of these cases as politically motivated and lacking credible evidence. In several instances, plaintiffs later admitted they had no knowledge of the journalists whose names appeared on the charge sheets.

Searches without warrants allowed

One of the most urgent demands from post‑revolution civil society was the full repeal of the legal instruments historically used to criminalise dissent. Although the interim government announced its intention to repeal the Cyber Security Act in late 2024, the drafting of the “Cyber Protection Ordinance (CPO) 2025” and the “Personal Data Protection Ordinance 2025” quickly generated new anxieties.

The CPO is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It retains the same vague language of the discarded Digital Security Act, criminalising “intent to insult” and allowing warrantless searches. It has been widely criticised for retaining restrictive provisions inconsistent with Bangladesh’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Section 25 criminalises the transmission of information with the “intent to insult, harass, or defame” – a sweeping clause that can be deployed arbitrarily to suppress investigative journalism. Section 8 authorises the removal or blocking of content deemed harmful to “national unity” or “public order” without judicial oversight, while Section 35 permits warrantless searches and arrests.

The Personal Data Protection Ordinance 2025 has raised similar concerns. Its broad allowances for government access to user data have been described as granting “unchecked powers,” prompting fears among journalists that the law will facilitate mass surveillance of whistleblowers and media professionals. These legislative developments suggest a persistent instinct toward control, despite the change in executive leadership.

The illusion of reform

While the administration points to the establishment of the Media Reform Commission, the reality on the ground tells a different story. The Commission proposed goals like a “one owner, one media outlet” policy to promote diversity, the conversion of major media houses into publicly listed companies to enhance transparency, and the creation of an independent National Media Commission to replace existing regulatory bodies long criticised for political influence. The commission also advocated for a minimum wage for journalists, aligned with the pay scale of Class 1 civil service officers, to reduce vulnerability to bribery and political pressure.

Yet despite the ambition of these proposals, implementation has been slow and uneven. Media analysts noted that even as the commission was drafting its report, the interim government approved new television licenses through the same opaque and politically influenced procedures used by previous administrations. This disconnect underscored the widening gap between the rhetoric of reform and the realities of governance.

Institutional and legal pressures

A particularly contentious development during this period was the creation of the “CA Press Wing Facts” unit under the Office of the Chief Advisor. While the government presented the unit as a mechanism for fact‑checking and combating disinformation, media‑rights organisations described it as a de facto censorship authority. Critics accused the unit of “manufacturing the government’s version of truth” and intimidating media houses and civil society groups by publicly discrediting their reporting.

Even the International Crimes Tribunal became a venue for these grievances, with complaints filed against 32 senior journalists accusing them of “inciting genocide” through allegedly sycophantic reporting during the uprising. The UN Human Rights Office and several international rapporteurs have urged the authorities to withdraw what they have called “baseless” criminal charges against media professionals.

Global and domestic outcry

To grasp the extent of the challenges facing Bangladesh’s media since the formation of the Yunus interim government, one also needs to look to the statements issued by leading international human‑rights and press‑freedom organisations – Amnesty International, Reporters Sans Frontières, and others. Their assessments are unequivocal. They describe a media landscape closing at alarming speed, a climate of fear tightening its grip, and escalating dangers for anyone who dares to speak openly. The message is unmistakable. The stakes are rising rapidly.

Amnesty International has publicly urged the Yunus‑led interim government to safeguard freedom of expression, warning that journalists across Bangladesh are facing persecution, intimidation, and a rapidly shrinking civic space. In one of its research findings, Amnesty observed:

“Despite initial pledges to restore freedom of expression and uphold democratic values, Yunus’s administration has presided over a deepening assault on press freedom. Journalists, both in urban and rural areas, are now facing threats, fabricated charges, detentions, and brutal attacks. Old laws like the Digital Security Act, once condemned by Yunus himself, remain in force. New regulations, framed in the name of ‘digital safety,’ risk further gagging the media.” (Bangladesh: The fallacy of media freedom under Yunus regime, December 2025)

RSF has issued repeated warnings that press freedom in Bangladesh has come under severe strain during the current interim administration. Their statements highlight wrongful accusations against journalists, misuse of legal instruments, and the urgent need for structural reforms. One RSF report noted:

“While the interim government’s takeover in August 2024 raised hopes for improvement, journalists’ safety remains unprotected. They are being assaulted while reporting, subjected to physical retaliation for their articles, and their newsrooms are being stormed by protesters. RSF calls on the authorities to prosecute all those responsible for these attacks, to put an end to this intolerable cycle of violence, and to ensure the safety of media professionals.” (Bangladesh: violent attacks on journalists are surging – the government must take action, February 2025)

RSF has also directly urged Muhammad Yunus to uphold his government’s promise to protect journalists, stressing that the state has a duty to ensure fair trials and guarantee that media professionals can work safely, independently, and without fear of legal retaliation.

A pervasive climate of fear

The Commonwealth Journalists Association has echoed these concerns, adding further weight to the growing international alarm. In its recent statements, the CJA warned that pressures on Bangladeshi journalists have reached a critical point, placing both their safety and the integrity of independent journalism at serious risk. One of its reports bluntly stated:

“Journalists right now in Bangladesh are in fear of losing their jobs, being arrested or worse, being a victim of mob justice.” – (Legal moves thwarted in Bangladesh as journalists kept in detention) The International Federation of Journalists has similarly documented escalating threats in the aftermath of major political upheaval. Their reports describe a media environment marked by intimidation, legal harassment, and a pervasive climate of fear that persists even under the interim administration. The IFJ has stressed that Bangladeshi media “must be free to report without fear of retaliation,” and that genuine plurality of voices must be protected throughout the interim government’s tenure.

Seven international organisations – Access Now, BLAST, Human Rights Watch, ITJP, JDS, and the Tech Global Institute – have jointly condemned violent attacks on Bangladesh’s media houses, calling them a grave threat to freedom of expression. Their statement highlighted a documented pattern of repression: abuse of the legal system, intimidation of journalists and artists, and attacks on bauls (sufi song singer) and media workers throughout the year.

They also warned of rising extremism, fuelled by online hate speech and explicit calls to violence from influential social media personalities. This content, amplified by followers and affiliated networks, underscores the technology sector’s failure to meet its human rights responsibilities and its chronic underinvestment in user safety across the Global Majority.

The State’s failure to respond

The organisations held the authorities responsible, noting that the state has repeatedly failed to respond promptly or effectively to online hate and incitement, despite well-established patterns of violent mobilisation.

The alarm is not only international. Inside Bangladesh, respected voices are raising the same concerns. Mahfuz Anam, Editor of The Daily Star, recently wrote:

“While 18 journalists were arrested without any specific charges, the more acutely embarrassing reality is that at least 296 journalists have been implicated in unsubstantiated criminal cases, many of them for murder… the present interim government has inflicted another kind of humiliation on us by allowing the largest-ever judicial harassment of journalists in our history… we find it deeply troubling that Bangladesh appears to have one of the highest numbers of journalists accused in murder cases in recent times.” (End impunity, uphold press freedom-1 November 2025)

These concerns are not abstract—they are documented in detail by multiple organisations, each presenting stark evidence of the scale of repression now facing the media.

Transparency International Bangladesh reported that at least 1,073 journalists and media workers were subjected to attacks, lawsuits, killings, threats, harassment, detention, or job loss in 476 separate incidents between 5 August 2024, immediately after the July mass uprising, and 1 November 2025. (The State of Media in Post-Authoritarian Bangladesh- December 2025)

On World Press Freedom Day 2025, the Rights and Rights Analysis Group released a damning assessment titled “Bangladesh: Press Freedom Throttled Under Dr Muhammad Yunus, May 2025”. The report exposed a systematic campaign to silence dissent under the interim government. According to RRAG, in just the first eight months of Dr. Yunus’s administration, 640 journalists were targeted through various forms of repression: 182 faced criminal charges, 206 were subjected to physical violence, 167 were denied accreditation, 107 journalists were investigated by the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit on questionable money‑laundering allegations.

Normalisation of mob intimidation

Beyond legal harassment, journalists also faced arbitrary dismissals—often under pressure from the Anti-Discrimination Students Movement, a group whose influence has grown in deeply troubling ways. Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK) recorded harassment or abuse of at least 381 journalists. Of them, 123 faced legal cases, 118 were physically attacked, 20 received death threats and 23 were targeted by law enforcement. Three journalists were killed, while the bodies of four others were recovered under mysterious circumstances.

Manabadhikar Shongskriti Foundation documented 289 incidents affecting 641 journalists, including one killing, injuries, threats and legal harassment. It also cited the continued use of the Cyber Security Act and ordinance to file cases against journalists.

ASK recorded harassment or abuse of at least 381 journalists. Of them, 123 faced legal cases, 118 were physically attacked, 20 received death threats and 23 were targeted by law enforcement. Three journalists were killed, while the bodies of four others were recovered under mysterious circumstances.

Taken together, these findings reveal a stark and deeply unsettling reality: Bangladesh is witnessing a coordinated and escalating assault on the press, enabled by legal instruments, administrative coercion, and the growing normalisation of mob intimidation. The pattern is unmistakable—and profoundly alarming for anyone who believes in the basic right to speak, report, and question without fear.

The period from July 2024 to January 2026 has exposed a painful contradiction. The promise of renewal that followed the uprising has instead laid bare the fragility of the rule of law in a revolutionary moment. The rise of mob justice, the weaponisation of murder charges against media professionals, the purging of journalists from public life, and the drafting of new restrictive cyber laws all point to a political culture where the reflexes of control and intolerance remain deeply entrenched.

As Bangladesh approaches its 2026 national elections, the future of its democracy hinges on whether the interim government can move beyond the rhetoric of “revolutionary justice” and guarantee that journalists can inform, educate, and empower society without fear of violence or reprisal.

What is unfolding today has no precedent in the country’s history. When mobs can burn media houses, storm cultural institutions, and terrorise journalists with impunity, and when the state responds with silence or symbolic gestures, the message is brutally clear: Bangladesh is becoming a hostile environment for truth.

This is no longer a passing crisis. It is a defining struggle over the character of the nation itself. Will Bangladesh become a country where journalists are jailed for reporting, where cultural institutions are attacked for promoting pluralism, where mobs dictate the boundaries of public discourse while the state looks away? Or will it reclaim the values that animated its liberation -secularism, democracy, and freedom of expression?

The answer depends on what happens now. The demands are clear, urgent, and non‑negotiable:

- Free all imprisoned journalists without delay

- Drop all fabricated charges against media workers, writers, and cultural activists.

- Launch transparent, independent investigations into every attack.

- Prosecute the perpetrators, every single one.

- Ensure international monitoring of Bangladesh’s human rights obligations.

Bangladesh’s democratic future is being tested in real time. Silence is surrender. Only decisive action can chart a different path.