By former CJA President Mahendra Ved

26/1/26

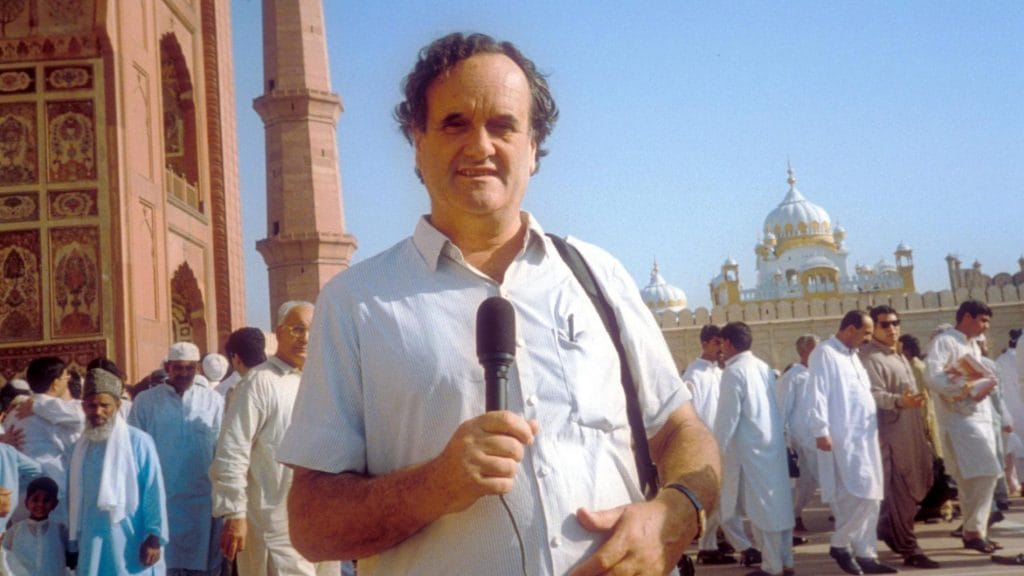

The renowned BBC journalist Mark Tully spent decades reporting on India, and has died in Delhi.

“Hello Mark” was how everyone greeted him wherever he went across South Asia. They included at least two prime ministers whom I had noticed way back in 1974, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of Bangladesh, who welcomed him with a hug. There must be many more.

Over three generations, it was impossible for the heads of government, whether or not they liked him and his reporting, not to know Sir William Mark Tully.

Millions listened to him. The BBC should, naturally, be popular, given the South Asian region’s colonial past. Scores of journalists reported, wrote, broadcast and filmed for it. But Tully kept the BBC flag flying, long after India and the rest of South Asia became independent, amid a plethora of foreign media bodies, old and new.

A storyteller

A White man with no airs, he belonged to those he worked with, which came naturally to him. A journalist, he was a storyteller of a different type, like Ruskin Bond, another Briton, who has made India his home.

For the Indian scribes, and I guess across South Asia, he was like “apna banda” (our man). Several grew to admire him.

I must confess, Mark’s fame and popularity once made me extremely jealous. In 1991, we were reporting on Bangladesh’s parliamentary elections. Results out, I waited four days to interview the winner, Begum Khaleda Zia. I had known her husband, President Ziaur Rahman, even reported his presidential election, but that did not help. She had apparently been briefed negatively about my being an old Dhaka-hand of the 1970s vintage. She finally came on the phone to express a word of regret and say she was “very busy”.

Disappointed, I headed for the airport, and who do I meet? Mark and I had a long chat till we boarded. He revealed that he had “a very pleasant lunch, over two hours” with the incoming premier.

I realised the futility. Mark’s journalism was different from mine. A friendly Bangladeshi journalist once jokingly taunted me that I was a practitioner of “Sub-continental” and “not inter-continental journalism.”

Sadly, my last meeting and my introduction of Mark were virtual, not in person. I was hosting the international conference of the Commonwealth Journalists Association (CJA). With the most valuable intervention of Satish Jacob, his long-time friend and colleague, I persuaded Mark to deliver the Valedictory Address. Although not keeping too well, he agreed.

Wanting to make the best of it and to bring down the monotony of the proceedings, as I was stepping down, I made Mark’s introduction less presidential and more like a Bollywood buff.

I switched to the famous Shashi Kapoor line delivered to his rich-bad brother Amitabh Bachchan, who demands, in the film Deewar (1975): “I have so much money and power, what do you have?” The honest cop Shashi replies with the ultimate put-down: “Merey paas Ma Hai” (I have mother with me).

I declared to the global gathering of those routinely listening to the BBC, and revering him: “Merey paas MARK Hai.” (I present you Mark)

RIP, Mark!

The journalist who taught India to the BBC

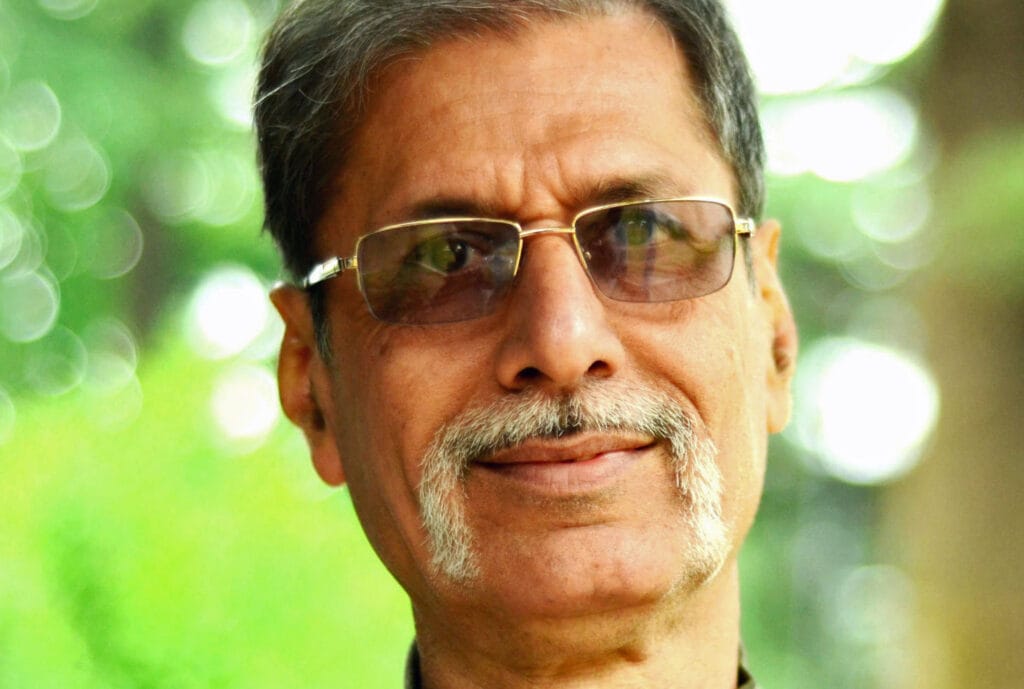

By Mark Tully’s former BBC colleague, SUBIR BHAUMIK

A day before he passed away, Mark Tully’s condition was described by his partner Gillian Wright as “stable but critical.” I was intrigued by Gilly’s message on WhatsApp, but knowing how she would be feeling, I decided not to question her any further. Perhaps she was trying to put up a brave face, knowing the inevitable was near.

Mark was 90 and had not been well for a while. His love for everything Indian was part of the problem. Gilly would often complain of health problems caused by his love for Indian curries, but Mark was unfazed.

His ability to take the rough with the smooth with that same unfailing smile made him what he was. Nothing really mattered; it was all part of life.

The BBC’s human face

For me and many of my South Asian colleagues who made a name working for the BBC at a time when it when it was the “go-to media option” for millions across the subcontinent, Mark was the father figure, the mentor and the teacher who made it all possible. He believed in South Asian talent, trusted our regional expertise and never imposed himself on us, unlike some of the over-rated bigfoots arriving from London with the know-all swagger.

At the end of the day, Mark was a deeply humble man who knew the huge complexities of the region could be handled by the BBC only if the London bigwigs trusted the field correspondents in the regions. At the same time, he taught us how to ‘market’ our stories, how to fit them into the big picture. We became global by remaining local, grounded but aware of why something here mattered for audiences elsewhere.

When Mark’s second-in-command in the BBC Delhi bureau, Satish Jacob, another great friend and colleague, walked me into his office-cum-residence at 1, Nizamuddin in Delhi one summer afternoon in 1986, I had expected a British burra sahib in a suit. To my surprise, I found a smiling man in a kurta-pyjama asking me in Hindi, “BBC mein kaam karenge?” Mark made an extra effort to give us the feel that the BBC was as much ours as his — and for that feeling to prevail, he would relentlessly stress the value of the language services in radio as the key to the BBC’s global outreach and acceptability.

His despatches, when used in these language services, made him a media icon from Peshawar to Yangon — a voice audiences could trust. Mark read Indian newspapers closely and marked out good regional reporters whose coverage stood out. They would then be approached and offered stringerships. When they had shaped up well, they would be asked to join the staff. Mark prioritised regional network expansion and then trained us to BBC standards, both through formal training sessions and hands-on everyday counselling. He was a network builder par excellence.

A rebel with principles

There were some other contemporaries of Mark Tully who felt the same way – William Crawley, the historian David Page and the late Alexander Thomson. They had their differences, but for us in the field, they provided a unique media ecosystem where talent and capability mattered, where a big story in your region could effortlessly sail into the global headlines with ease. When your boss(es) understands the region, it becomes so much easier to do that.

Mark Tully studied theology at Cambridge, but, thankfully for the world of broadcasting, he did not end up in the Church. He was the BBC’s longest-serving South Asia bureau chief – 20 years at the he helm, 30 years in all. He would have gone much higher in the BBC but decided to stay back in Delhi. “I am much more interested in India and the region than in climbing the BBC ladder,” he would famously say.

Stories of Mark’s exploits abound, and, honestly, they are far too many. It would make for a book by itself. He left the BBC in a huff in 1994 after falling out with its new cost-conscious management when he famously said, “The BBC has been invaded by accountants.”

Standing up to power

At the heart of the differences was Mark’s reluctance to be seen as an ‘also-ran’. He wanted the BBC to break big stories, come up with scoops, do great documentaries – something that audiences would talk about for years to come and remember. He wanted to lead the pack but failed to convince the ‘accountants’ he hated so much that the pursuit of quality cost money, and if they were not willing to understand, he would leave, but not compromise.

Mark also would not compromise on professional integrity. He refused to budge during the Emergency by playing it down and was thrown out by Indira Gandhi’s government, only to return as a hero.

Mark left the BBC, but the organisation often found itself compelled to fall back on his expertise. When I scooped the story of Mother Teresa’s death and the BBC decided to do a whole day of live coverage of her funeral in Kolkata, they brought in Mark Tully as the expert and Nik Gowing as the lead anchor. Nik had been anchoring the coverage of Princess Diana’s death for a week before Mother Teresa’s death. As both met up with me at our makeshift studio in Hotel Peerless, Mark asked me to take them to the Calcutta Coffee House for “an adda with the Dadas.” “Nik needs to get Diana out of his system and get a hang of Calcutta, and I need to catch up,” Mark said.

A master story teller

The next day, the BBC’s coverage of Mother Teresa’s funeral was actually a real insight into the unique city for a global audience and stood out against other foreign media. On Mark’s insistence, I had to even get a Ramkrishna Mission monk and a Muslim Imam to the BBC makeshift studios to discuss the legacy of Mother Teresa and the city that made her.

That is how Mark worked. Thorough research, endless recces to get the feel of the subject, talk to everyone relevant for the story, but most important of all, his uncanny ability to tell the story in simple language for a mass audience in a way all would understand.

In the last few years, as I met Mark during my visits to Delhi for the occasional lecture, he would feel sorry at the demise of the BBC as a global media power. And he would deeply worry about India and its future. Deeply mourned by his former colleagues and tens of thousands of friends, Mark will go to his grave with no ‘full stops’. A life lived in full and with honour.

- Subir Bhaumik’s tribute to Mark Tully first appeared on the Indian website The Federal.

- Mark Tully’s coverage of momentous developments in South Asia:

https://www.facebook.com/share/r/1DX9CpKykk/?mibextid=wwXIfr - Extracts from some of Mark Tully’s reports, and a tribute from his colleague Sam Miller. https://www.facebook.com/reel/1344977040996897

- Former BBC Delhi correspondent Andrew Whitehead shares his memories of Mark Tully https://www.youtube.com/shorts/49ARPCi710Q